Why I stopped using HRV apps

I loved the idea of an app that could tell me to train or not to train, to go easy or go hard. I liked the convenience of one train-or-don’t-train metric. It would take away the second-guessing and keep me healthy as well. Right?

Unfortunately, it didn’t work out that way.

The HRV Apps

I started with Elite HRV (because it’s free) and then moved on to ithlete (because it’s nicer to look at). Elite HRV distinguished between sympathetic and parasympathetic biases in the central nervous system. ithlete’s Pro account gave more nuanced prescriptions with its Z-scoring.

But for what I needed—reliable daily training advice—neither was foolproof. Elite HRV recommendations didn’t seem to vary that much. ithlete often told me to train when I felt tired.

The Test

Late last year, I did a daily comparison between Elite HRV, ithlete, and an orthostatic heart rate test. The HRV apps are quick and simple, but an orthostatic heart rate test is far less convenient. It takes longer and it requires ongoing interpretation, but I’d had good results with it in the past. After variable results with the apps, I was willing to try something more cumbersome, as long as it was effective.

In particular, I wanted to look for false positives in any of the three methods. While a false negative—telling me to rest when I could train—could lead to undertraining, a false positive would be far worse. False positives—telling me to train when I should rest—would lead to overtraining. That would mean lost training time due to excessive fatigue or illness or both.

The test method I used was:

- After waking, I put my on heart rate monitor, lay down, and let my heart rate stabilize; then

- I did the 2.5-minute Elite HRV test; then

- the 55-second ithlete test; then

- the ~4-minute orthostatic test.

The orthostatic heart rate test consisted of:

- Recording my average heart rate over the first 2 minutes; then

- Standing up and recording my peak heart rate; and finally

- Recording my heart rate 1 minute after the peak.

The Results

Each day I recorded the recommendations of each test method. I added up the “votes” from the tests to come up with a total for the day. As the weeks passed, it became clear what the character of each method was:

- The orthostatic heart rate test (OSHR) was the most conservative. It regularly gave me “red lights,” indicating that I should rest. “Yellow lights” were even more common, suggesting easy recovery days.

- Elite HRV had a more mixed response, not as pessimistic as the OSHR and not as optimistic as ithlete. I like that Elite HRV distinguishes between sympathetic and parasympathetic biases in each reading.

- ithlete was the most aggressive and, therefore, the most concerning. A training readiness test should adopt a do-no-harm policy. ithlete appeared to prefer a train-as-much-as-possible policy.

Two instances in particular confirmed my suspicions about the HRV apps, one with ithlete and one with Elite HRV. In each instance, I was particularly fatigued and it was obvious that I needed to rest. In contrast, the apps recommended that I train.

ithlete

Of the two HRV apps, ithlete was definitely the more aggressive in its recommendations. It rarely gave me the red light, while the other two methods were more varied.

I did a lactate test on November 12 where my heart rate reached over 95 percent of maximum. (My max heart rate is over 200, and I reached 199 during that test.) Three days later, I was still tired, and it felt obvious that I needed a rest day. Both the orthostatic test and Elite HRV agreed.

Not only did ithlete recommend a training day on November 15, it did even worse. It suggested that my training should be high intensity.

ithlete doesn’t distinguish between biases in the central nervous system. That may explain the bad recommendation. ithlete seems to interpret sharp spikes in variability as enhanced adaptation rather than too much variability. I observed this on several occasions. It then recommends high-intensity training, the worst advice possible.

Elite HRV

Unlike ithlete, Elite HRV distinguishes between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. Each recommendation includes a sign of sympathetic or parasympathetic bias. If Elite HRV sees a sharp spike in HRV, then parasympathetic activity is elevated, and it says it’s time to go easy.

At first, I thought that Elite HRV did a good job of avoiding false positives, but it finally gave one in December.

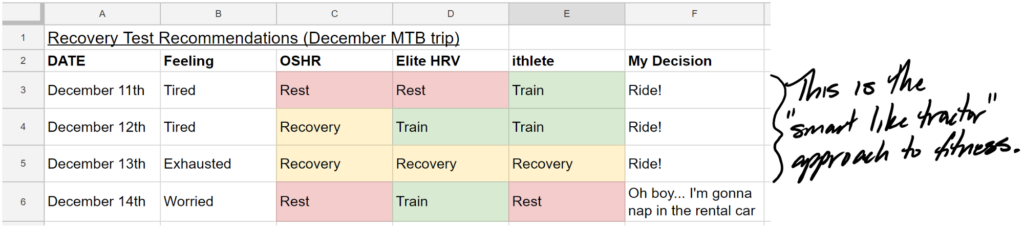

From December 11 to 13, I was on a mountain bike trip. Even before the trip started, I knew I hadn’t planned very well. I was too tired. It was a four-day trip, and we would be riding hard twice a day.

When I woke up on the fourth day, I knew that I had overdone it. I felt horrible, and I worried about getting sick. The orthostatic test and ithlete pointed to a rest day, but Elite HRV recommended training.

This is the “strong like bull, smart like tractor” approach to training: Even when you should rest, keep pushing! I went into this trip tired, and I knew it. The only readiness test that was faithful to how I felt was the orthostatic heart rate test. The other two were far too optimistic and, combined with my dumb attitude, dangerous.

In May 2019 Eric Carter, a member of the US National Skimo Team and a PhD candidate in physiology, recently sent us a study on HRV. Over five years, the study used 57 national-level Nordic skiers and compared their training loads with HRV readings. Their conclusion? "[We saw] no causal relationship between training load/intensity and HRV fatigue patterns."

The Orthostatic Test

Why have I assumed that the orthostatic test didn’t produce any false positives? Because whenever I felt like junk, the orthostatic test always raised red flags. It never indicated training when I was excessively fatigued. With “do no harm” as the priority, the orthostatic test was the only test that was faithful to that paradigm.

However, the orthostatic test does have a couple of disadvantages. First, the orthostatic method can take over 5 minutes while the apps are much shorter.

Second, readings are often uncertain “yellow lights,” even when I think I feel fine. That requires some careful interpretation to make the healthiest choice.

But I don’t see the longer test or the judgment calls as a disadvantage. I’d much prefer to be healthy and undertrained than fall over the edge into extreme fatigue and illness.

“It is remarkable how much long-term advantage [we]have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.” -Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway